It’s that time of the year again! With the dawn of the new year, comes elaborate and far-fetched lifestyle and fitness goals. Overzealousness with training and picking up new sports can potentially lead to overuse injuries and muscle strains. Getting injured early on while on the conquest of your new-year resolutions can dampen the motivation and stop you in your tracks. This blogpost serves to give some pointers on how you can safely dive into training.

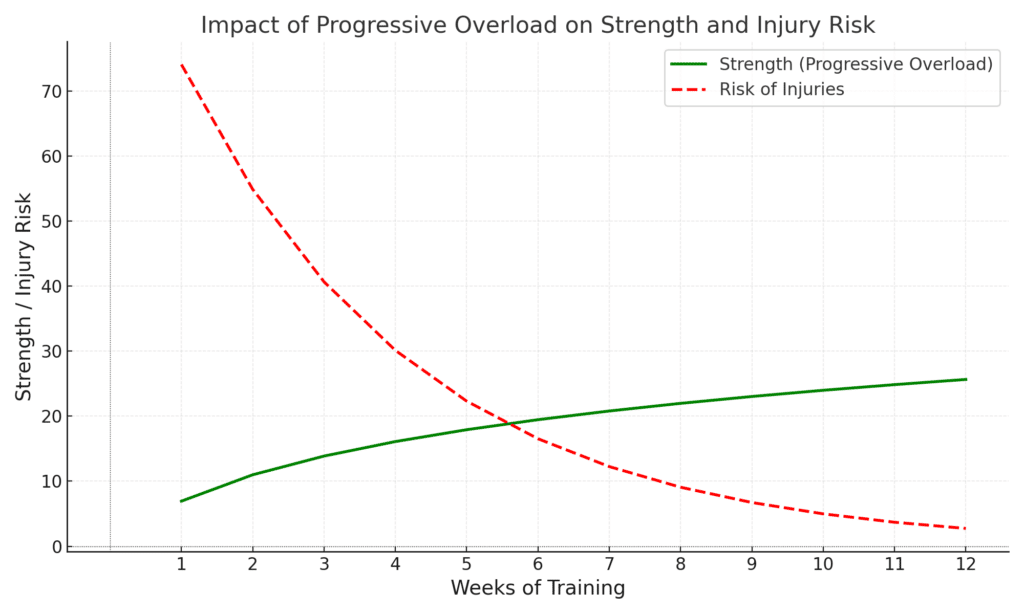

Injuries usually happen when we do things that we are not prepared for – doing something that we do not have the endurance or strength for. The key principle to mitigate such risks when getting into any new workout or sports routine is progressive overload. What is progressive overload? Progressive overload is a strategy used to increase the intensity of your workout and thus gradually placing more physiological stress on the body which leads to adaptations in strength and endurance. If the goal of working out is to get fitter, increase strength or slash a couple of kilos, progressive overload will be beneficial to help you achieve those goals.

You may have heard of the ‘10-15% rule’; a general guideline of increasing volume of training by 10-15% every week. Although there is little scientific evidence to support the use of this rule as a guide, the general population may benefit from it when trying to progressively overload. If you’re picking up a new sport, it’s important to lock in the technical aspect of it first before increasing intensity (i.e. practising the tennis stroke before going into gameplay). Having some baseline fitness would also go a long way!

Here are some ways you can implement progressive overloading into your workout:

Weights

- Having a 10-15% increase the total volume of your workout (i.e. increasing the number of reps done, using a heavier weight, increasing frequency of exercise in a week)

- Make the current exercise more difficult (i.e. adding tempo into the eccentric phase, adding pauses during the exercise, increasing range of motion of the exercise)

Running

- Increasing your total weekly mileage by 10-15% (i.e. if your total mileage in one week is 3km, you can increase your mileage to 3.3km the following week)

- Increasing the total volume of your runs (i.e. increasing the number of runs per week, speed or distance covered per run session)

- It is important to note that if you are just starting to run from not running at all, research has shown that a total weekly mileage of 3km can reduce the risk of overloading injuries in runners.

What can I do to reduce the risk of getting injured?

- Whenever in doubt while trying to progressively overload, always be more conservative. You do not always need to increase your workout volume every week, you can perform the same workout programme for 2-3 weeks before feeling comfortable to add increments.

- Listen to your body: If you are caught up with work and facing more stress or if you’re feeling more fatigued after continuous workout days, TAKE A BREAK. You will not lose out on gains if you miss one day of training. Physiological and psychological stress can affect your workout performance, increasing the risk of injuring yourself in the process.

- Ensure adequate recovery in between workout sessions. Recovery is important to ensure you are able to continue exercising regularly without running into burn-out. Also make sure that you have had sufficient sleep the night before as this will affect your energy levels while working out.

Hope this blog gives you some guidance on how to safely embark on your new health and fitness journey in 2025. Wish you all the best in achieving your fitness goals!

Key points:

- Pick up training or sports gradually, do not be overzealous when trying out something new

- Progressive overload is important to improve your ability to tolerate your physical activity volume

- Listen to your body! Do not go into the scenario where you do too much too quickly without any recovery and rest. This helps you stay consistent in continuing to exercise and reduce risk of injuries.

References:

Bertelsen, M. L., Hansen, M., Rasmussen, S., & Nielsen, R. O. (2018). The start-to-run distance and running-related injury among obese novice runners: A randomized trial. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 13(6), 943-955. doi:10.26603/ijspt20180943

Damsted, C., Parner, E. T., Sørensen, H., Malisoux, L., Hulme, A., & Nielsen, R. Ø. (2019). The association between changes in weekly running distance and running–related injury: Preparing for a half marathon. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 49(4), 230-238. doi:10.2519/jospt.2019.8541

Gabbett, T. (2017). Infographic: The training–injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(3), 203-203. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097249

Gabbett, T. J. (2018). Debunking the myths about training load, injury and performance: Empirical evidence, hot topics and recommendations for practitioners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(1), 58-66. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099784

Plotkin, D., Coleman, M., Van Every, D., Maldonado, J., Oberlin, D., Israetel, M., … Schoenfeld, B. J. (2022). Progressive overload without progressing load? The effects of load or repetition progression on muscular adaptations. PeerJ, 10, e14142. doi:10.7717/peerj.14142