Table of contents

- A Brief Overview

- What is Strength?

- What is Mobility?

- What is Flexibility?

- What Am I Lacking?

- Movement Screening

- Mobility

- Strength

- Flexibility

- Movement Screening

- Conclusion

This mini-series will be looking at strength, mobility, and flexibility as components of physical fitness. In this first part, we’re revisiting the definition of each component and applying it to dance, followed by a self-performed movement screening to put it into practice.

Part One: A Brief Overview

What is Strength?

Strength is generally defined as the maximum force that a muscle group can generate at a specified velocity. In a dance context, strength would refer to the ability to maintain the intended posture while performing dynamic movements. Being able to produce powerful and/or controlled movements, sustain muscle endurance, and generate speed to dance efficiently, all require aspects of strength.

Some subsets of strength often required in dance:

Endurance – slow and controlled movements, or sustained choreography

Power – fast movements with increased force exertion e.g. jumps, kicks, flips

Strength can be affected by several factors, such as age, gender, muscle fibre type. The ability of muscle fibres to contract, the connections between our muscles and nervous system, as well as the ability of our nervous system to control our muscles also affects strength.

What is Mobility?

Mobility is the ability to move a joint through a range of motion; a measurement of the distance a joint can move in the intended direction without external influence or momentum.

The joint capsule – a flexible, elastic membrane surrounding each joint – also affects mobility. Normal activities such as lifting your arm to wash your hair, or climbing stairs, puts normal stresses on the joint capsule via movements of the joint. These normal stresses are what maintains the flexibility and integrity of the joint capsule. The joint capsule may slowly tighten due to lack of normal stress, in situations where the joint is immobilized (post-surgery or after a fracture), or musculoskeletal conditions (e.g. bursitis, tendonitis) that restrict movement due to pain.

What is Flexibility?

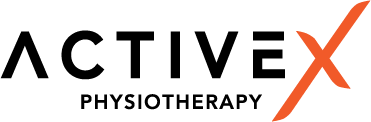

Flexibility is the ability of a muscle to lengthen through a range of motion.

- Passive flexibility is the ability of a muscle to lengthen with outside influence (e.g. gravity, equipment, partner) beyond the involved joint’s end range of motion.

- Active flexibility is the ability to utilize the strength of surrounding muscles to perform or hold a stretch.

The easiest example is to look at the splits. When we sit in our front splits (on the floor or in oversplits) to stretch, we are utilizing passive flexibility. Active flexibility is what is required to be able to create that full split during a grand jete.

Side note: flexibility is different from muscle elasticity. Muscle elasticity is the muscle’s ability to recover to their original form upon removal of the force initially applied, i.e. the ability of muscle fibres to contract rapidly after extension. It is linked to power and explosive movements, which we will discuss in future posts.

Now that we have a better understanding of what each component is, let’s ask ourselves: how do I measure up against expectations for strength, mobility, and flexibility?

Part Two: What Am I Lacking?

Let’s try a quick movement screening!

A quick note that these are a just sample, and not an exhaustive menu of assessment tools we use to assess (1) Mobility, (2) Strength and (3) Flexibility.

(1) Mobility

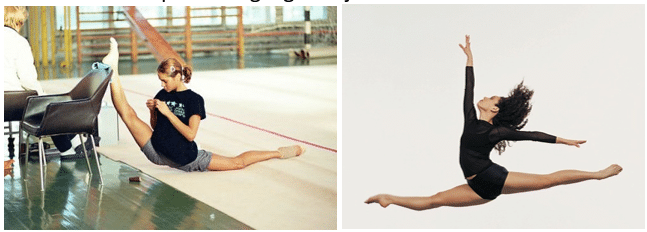

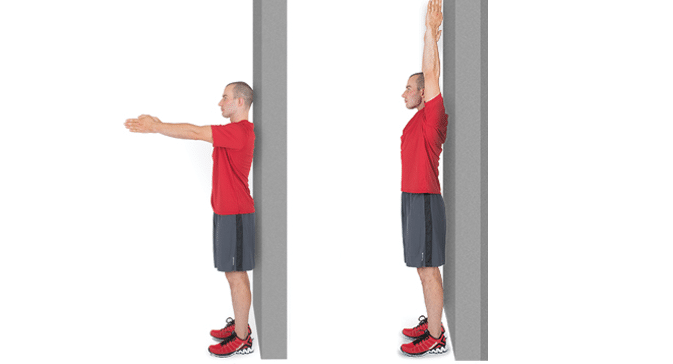

Shoulder

Active Shoulder Flexion Range

- Stand (or sit) with your back flat against a wall.

- Raise one hand overhead until you feel your back beginning to leave the wall.

- Compare shoulder flexion range on both sides.

Active Shoulder External Rotation Range

- Stand with your back flat against the wall, back of wrists and elbows touching the wall (shoulder abducted 90°, shoulder externally rotated 90°.

- Extend your hands overhead while keeping elbows, wrists and back in contact with the wall.

Result Interpretation

Normal shoulder flexion and abduction range is 180° (arms beside ears).

Normal shoulder external rotation range is 90°.

Try to pinpoint where you feel restriction (does it feel like pain or tightness) if your shoulder range is limited.

Hip

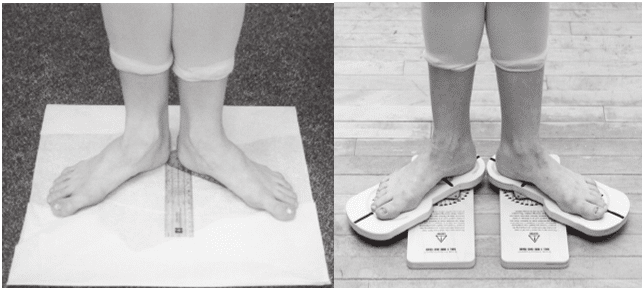

Active Turnout in Standing

- Stand in your normal first position (check to make sure that pelvis, spine and feet are neutral).

- Measure the angle between the shaft of the second metatarsal and the midsagittal plane. Alternatively, you can stand on a flat goniometer. Rotational disks can be used as a comparative measurement as well.

- Measuring parallel, second, fourth and fifth positions in standing will also provide useful comparisons to the baseline measurement in first position.

Passive Turnout

- Lying flat, have a second person (the tester) externally rotates your leg until they perceive the capsular end-feel in the hip joint. Keep both hands on your iliac crests (hip bones), do not allow your pelvis to rotate, and keep your knees straight. Make sure you are relaxed as the tester should be the one moving your leg.

Result Interpretation

The average non-dancer usually has turnout of 40-45°, with dancers averaging 55° and occasionally slightly more. Few dancers are able to achieve full 180° turnout in first position without compensating by rolling their feet or excessively twisting from the knee down. The International Association of Dance Medicine and Science (IADMS) states that on average, 60% of turnout comes from the hip, 20-30% from the ankle, and remaining 10-20% from the knee and tibia.

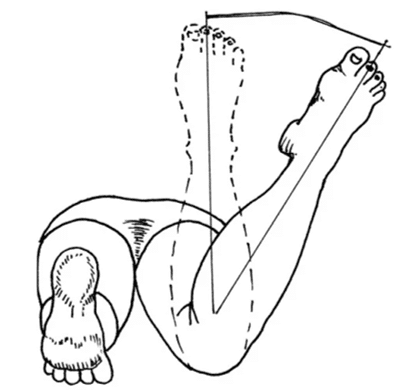

Hip Internal Rotation (active and passive range)

- Lying face down, bend your knee to 90 degrees, and internally rotate as much as you can without lifting your hips or knee off the ground. This is your active range for internal rotation.

- Repeat the movement, this time with a second person (the tester) performing the movement to assess your passive range of motion.

Hip External Rotation (active and passive range)

- Lying face down with knee bent to 90 degrees, externally rotate from your hip without lifting your hips or knee off the ground. This is your active range for external rotation.

- Have a second person (the tester) repeat the movement while you are relaxed, to assess your passive range of motion.

Result Interpretation

Normal hip internal rotation: 30-45° (in dancers: ranges from 5-50°)

Normal hip external rotation: 40-50° (in dancers: ranges from 30-80°)

Difference between active and passive ranges can be a sign of tightness, or weakness.

Ankle

Ankle Dorsiflexion

- Measure the maximum distance of your big toe from the wall while keeping your knee in contact with the wall, foot straight, and heel firmly planted on the ground.

Result Interpretation

Each centimeter corresponds to approximately 3.6° of ankle dorsiflexion. A distance of at least 12.5cm is considered normal (dorsiflexion angle of > 20°). If the difference between right and left measurements is more than 1 finger’s width, it is considered significant.

(2) Strength

When assessing strength, the most accurate measurements are obtained from handheld dynamometers. However, for this post, I have included bodyweight movements that can be done easily in a home or studio environment.

Shoulder

External Rotation

- Lying face up with the dynamometer placed just above the back of the wrist, push upwards with the back of your wrist as hard as you can.

Internal Rotation

- Lying face up with the dynamometer just below the wrist, push down as hard as you can (like you’re trying to bring your palm to the floor).

Result Interpretation

Shoulder internal/external rotational strength ratio is typically 1.3-1.5.

In sports involving upper body or overhead movements, the ratios are higher e.g. 1.5 in tennis players, 1.6-2.2 in baseball athletes.

Hip

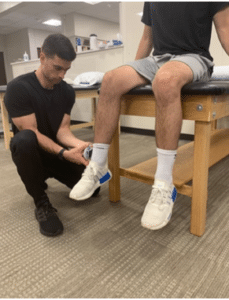

External Rotation

- Sit on the edge of a stable surface, with the dynamometer positioned just above the medial malleolus.

- Push inward with the inside of your ankle as hard as you can, keeping your thigh down on the plinth or table.

Internal Rotation

- Sit on the edge of a stable surface, with the dynamometer positioned just above the lateral malleolus.

- Push outward with the outside of your ankle as hard as you can, keeping your thigh down on the plinth or table.

Result Interpretation

Expected ratio of external to internal rotation strength: 1.08 for males, 1.16 for females.

Limb Symmetry Index (LSI): [(strength of weaker side) / (strength of stronger side)] x 100

- The absolute value of this score is the strength asymmetry score

- A LSI of >10% indicates strength asymmetry

Lateral Step Down Test

- Standing at the edge of a 20 cm step, bend the knee on the step until the heel of your non-testing leg touches the floor.

- Without applying any weight on your heel, immediately straighten the knee of your testing leg to return to the starting position. Repeat for 5 repetitions.

Result Interpretation

Poor movement quality (e.g. hip drop, trunk side bending, knee deviating medially) has been associated with deficits in hip external rotation and knee extension strength, as well as limitations in ankle dorsiflexion range of motion.

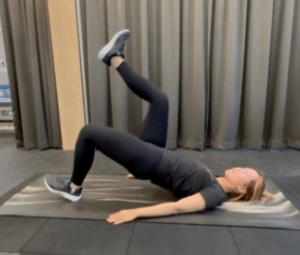

Single Leg Bridging

- Lying on your back with one leg off the floor, push through your heel and lift your hips to perform a single leg bridge.

- Check for neutral lumbar spine, level hips (i.e. no tilting or dropping to one side), and equal length on both sides of your waist.

Result Interpretation

Poor movement quality denotes poor lumbo-pelvic-hip stability. This can be contributed by weakness of the deep lumbar extensors, glute maximus and medius, and hamstrings.

Core

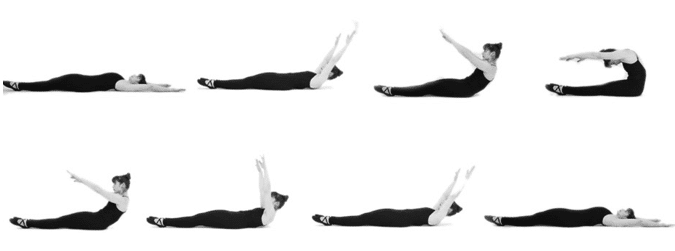

Pilates Roll Up

- Lying flat with hands overhead, start bringing your hands over your shoulders. Once your arms are perpendicular to the floor, start rolling yourself up and off the mat (think of peeling yourself off), one vertebrae at a time, while maintaining a big C shape throughout your spine.

- Once you reach a sitting position with your arms parallel to your legs, reverse the movement in a controlled manner and return to lying down.

Result Interpretation

Requiring use of momentum signifies weakness in your deep core muscles. If your spine flattens out during the roll up or down (i.e. unable to maintain spine flexion in the big C curve), there is likely tightness in your thoracic or lumbar spine segments.

(3) Flexibility

Spine

Pilates Prone Press Up (Thoracic Spine – assessing both mobility and flexibility)

- Start with hands under your shoulders, spine fully relaxed. Inhale and lift your head to initiate the spine extension, pressing your hands on the ground.

- Continue extending your thoracic spine until only your bottom ribs are in contact with the ground. Your lower back should still be fully relaxed.

Result Interpretation

Compensatory movements such as shrugging shoulders, lifting stomach off the ground, or use of lumbar extensors signifies that thoracic spine is stiff.

Backbends

Option 1: Backbend against a wall

Option 2: Bridge backbend

Result Interpretation

We are looking at the distribution of the spinal curve, i.e. does most of the curve come from your lower back, or is there an equal curve throughout your spine?

In a bridge backbend, we are also looking at:

- Distance from your palms to your feet

- Whether your feet are parallel or turned out

- Ability to stack shoulders over wrists

Hamstrings

Front Splits

Result Interpretation

Inability to straighten your front leg, or square your hips signifies hamstring tightness of the front leg. Being unable to straighten your back leg implies tightness of your hip flexors.

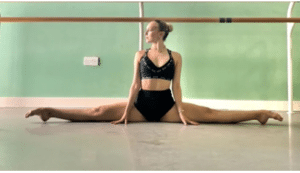

Adductors

Result Interpretation

Tightness of your adductors limits the range (or width) of your centre split.

Conclusion

Strength, mobility, and flexibility are just a few components that every dancer needs in their toolkit. There are other physical fitness components such as aerobic and anaerobic capacity, agility, speed, and balance that we should not overlook in our training as well. To be an all-rounded dancer, our training in and outside of the studio should try to target as many of these components as possible.

Now that we know more about each component, and we’ve done some assessments, the next question is: how does this affect me as a dancer?

Stay tuned for Part 2, where we’ll be looking at implications for injury, as well as training guidelines for strength, mobility, and flexibility.

Leave a comment on our Instagram post and let me know your thoughts after reading this post, or if there’s any topic you’d like to see discussed in upcoming articles!