What is Plantar Fasciitis?

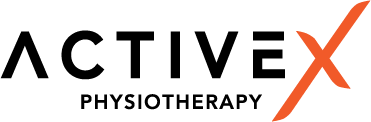

The plantar fascia supports the medial longitudinal arch of the foot and absorbs shock during weight-bearing activities. It originates at the calcaneus (heel bone) and inserts into the metatarsal heads of each of the 5 digits. During weight-bearing activity, the plantar fascia is stretched and loaded.

It affects 4-7% of the population and is predominantly seen in the sedentary middle-aged to older population, rather than the athletic population.

Excessive mechanical loading through the plantar fascia, whether it’s an increase in weight-bearing activity (walking or running) or wearing shoes with less arch support, can cause plantar fasciitis. Despite its name, plantar fasciitis is actually not an inflammatory condition; there is an absence of inflammatory cells. This condition is primarily a degenerative process. Imaging shows microtears, collagen disarray/disorganization and thickening of the tissue, reducing the plantar fascia’s ability to bear load, which can result in pain.

How do I know I have Plantar Fasciitis?

Plantar fasciitis is typically characterised by:

- Pain at the heel and/or over the medial aspect of the plantar fascia during weight-bearing

- Pain during the first few steps in the morning or after prolonged non-weight-bearing activities (e.g., prolonged sitting). The pain eases with movement until the load becomes too much for the plantar fascia to handle, at which point the pain re-emerges.

- It typically presents unilaterally, but as many as 30% of people can have it bilaterally.

Risk factors for Plantar Fasciitis?

Load:

An increase in beyond what the plantar fascia can tolerate can cause microtears and pain. This may be from increased walking/running mileage, speed, or even changing shoes (e.g. less cushioning, less arch support, or a lower heel drop encouraging a rearfoot strike).

To address this, your Physio will perform a thorough subjective assessment to pinpoint the cause. This may include a temporary reduction in weight-bearing activities to de-load the plantar fascia before gradually building up the load again while keeping symptoms at bay.

Running Mechanics:

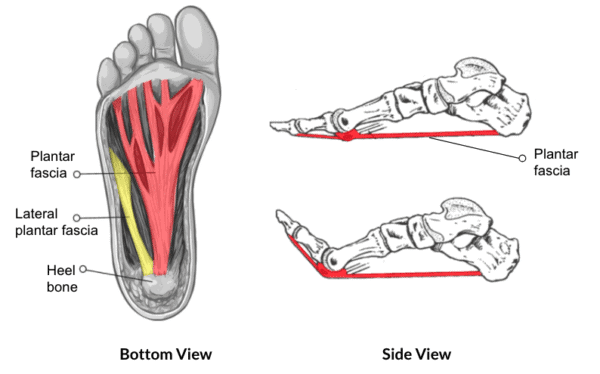

Rearfoot strikers place more stress on the plantar fascia from initial contact to push-off compared to forefoot strikers due to the windlass effect. The windlass effect occurs when the toes are dorsiflexed, stretching the plantar fascia and allowing the foot to form a rigid lever arm, which assists in a greater push-off during walking and running.

To address this, increase your running cadence (without changing the speed) to encourage a forefoot push-off. Once the pain resolves, you can gradually return to your previous running pattern, as long as it remains symptom-free.

BMI:

Plantar fasciitis is more prevalent in the sedentary population compared to the athletic population, likely because athletes’ plantar fascia has a higher baseline tolerance to load. Research shows a high BMI is not associated with plantar fasciitis in the athletic population, but there is evidence of an association in the non-athletic population.

To address this, aim to reduce your BMI through diet (consult a nutritionist, dietitian, or coach) and increase exercise with low-impact activities like swimming, cycling, or weight training rather than increasing walking or running.

Foot Posture:

Regarding arch shape (pronated, neutral, or supinated), there is no direct association between foot posture and plantar fasciitis. However, once you have plantar fasciitis, a pronated foot can make treatment more challenging due to increased stress on the plantar fascia.

To address a pronated foot, low dye taping can be used. If this reduces symptoms, foot orthoses will be effective.

Alternatively, foot intrinsic exercises can be used to strengthen the muscles that support and lift the arch.

Toe push-ups. Individually move the big toe up & down 10 repetitions. Repeat to each individual toe.

How do I treat Plantar Fasciitis?

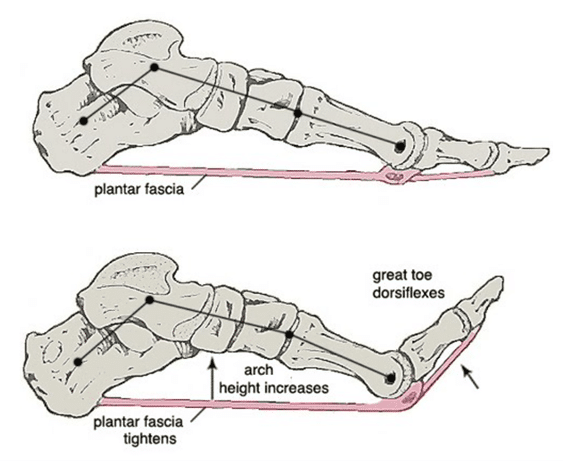

According to the British Journal of Sports Medicine, based on the best available evidence, expert opinion and patient voice, the best practice guideline is as below. If you have plantar fasciitis, the must-do for the first 4-6 weeks includes:

1. Plantar fascia stretching

Patients who stretched experienced improvements in both pain and function, especially in the first 2 weeks to 4 months. In the short term, there is moderate evidence showing this is more effective than shockwave therapy for pain reduction, although not in the long term. Stretches should be performed consistently throughout rehab.

2. Education

Your physio will provide specific education based on your individual risk factors and why you developed plantar fasciitis.

Since an increase in load is a risk factor, it’s important to temporarily reduce the overall tissue load during the early stages of rehab to reduce symptoms before gradually building up the plantar fascia’s load capacity. Wear cushioned and supportive shoes at all times (even indoors) until symptoms fully resolve.

3. Taping (Specifically low dye taping)

Moderate evidence suggests low-dye taping reduces pain in the short term. The goal of this taping is to lift and support the arches, reducing the compressive load on the plantar fascia when weight-bearing. If symptoms resolve with taping, orthoses or arch supports from a chemist or podiatrist may help maintain progress.

If symptoms haven’t reduced after 6 weeks, consider adjunctive interventions such as shockwave therapy, customized orthoses, or an injection. According to guidelines in Singapore, shockwave and PRP therapy may be considered before corticosteroid injections or surgery.

4. Shockwave therapy

Imaging shows that people with plantar fasciitis tend to have a 2mm thicker plantar fascia compared to control groups, often exceeding 4mm. Shockwave therapy (both focal and radial) has been shown to significantly reduce pain in the short and mid-term (12 weeks) and reduce plantar fascia thickness over the course of therapy.

Where does strengthening come in?

While resistance training is typically recommended for musculoskeletal injuries and tendinopathies, there is no strong evidence supporting or refuting its usefulness for plantar fasciitis. Some research shows reduced strength in foot muscles (hallux plantarflexion, ankle dorsiflexion, inversion, and eversion) in patients with plantar fasciitis, but the findings are mixed.

Since increased load on the plantar fascia is a risk factor, we encourage performing calf raises over a rolled towel to build up tolerance, and forefoot-elevated split squats to strengthen the muscles that support the longitudinal arch, further offloading the plantar fascia.

Above: Calf raises on a rolled towel to load the plantar fascia

Above: Heel elevated split squats with all digits on the plate. Focus on keeping the foot parallel to the ground.

Plantar fasciitis is a preventable and manageable condition. Understanding the underlying causes can help athletes return to their activities and reduce the risk of recurrence. Consult your physio to get your plantar fascia pain assessed and treated for a quick recovery.

References:

1. Morrissey, D. et al. (2020) Management of plantar heel pain: A best practice guide synthesising systematic review with expert clinical reasoning and patient values [Preprint]. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-36329/v1.

2. Tan, V.A. et al. (2024) ‘Consensus statements and guideline for the diagnosis and management of Plantar fasciitis in Singapore’, Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 53(2), pp. 101–112. doi:10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2023211.

3. Rhim, H.C. et al. (2021a) ‘A systematic review of systematic reviews on the epidemiology, evaluation, and treatment of Plantar fasciitis’, Life, 11(12), p. 1287. doi:10.3390/life11121287.