Welcome back to part 2 of our dive into Strength, Mobility, and Flexibility! Part 1 can be found here if you haven’t read it. In today’s post, we’ll be looking at:

· How these components of physical fitness play a role in dance-related injury prediction, as well as

· Guidelines for dance-specific training

Grab a snack, your favourite drink, and get comfortable. Let’s get into it!

INJURY PREDICTION

Strength

Technique classes can help in improving muscular strength and power, however it is not usually the main goal of each class. Newer formats of dance classes are increasingly asymmetrical, or are more focused on stylistic and artistic aspects of dancing rather than repetitive drills targeting strength, power and endurance.

Dancers need to be able to perform both slow and controlled movements (e.g. adagios, or sustained choreography in full-length productions), as well as movements requiring fast or sudden force exertion (e.g. jumps, kicks, stunts). The faster our bodies fatigue, the more challenging it becomes to control our limbs and keep up with the demands of the choreography. This then increases the risk of injury if one is not sufficiently prepared physically. Injuries from muscular imbalances, muscle strains, or overuse injuries are frequently seen among dancers.

Repetitive jumping, deep knee bends, muscle imbalances, repetitive knee hyperextension and forced turnout are some factors that contribute to an increased risk of knee injuries. Other factors include substandard footwear, poorly resilient dance surfaces, and long hours of practice. Excessive use was the most reported factor among most dance styles, due to the repetitive microtrauma that anatomic structures suffer when dancers practice through repetition.

In most dance genres, the highest frequency of complaints was in the thigh and lower limb. It was initially attributed to inadequate warm up for the lower body, however in recent years it is more likely that repetitive and/or sustained knee bending contributed to overload that surpassed the limit of its elastic capacity. In classical dance forms, other common locations of overuse injuries are the foot/ankle, hip, and low back. Interestingly, dancers trained in street dance styles had a higher frequency of upper limb injuries. This is likely due to increased tricks and spins performed using the upper body, compared to other dance styles with a heavy focus on lower body dominant tricks.

Mobility

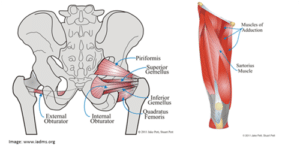

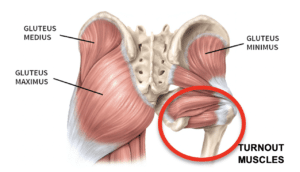

Classical dance genres (such as ballet, Chinese dance, Bharatanatyam) emphasise hip flexion, external rotation or turnout, and abduction, rarely adopting hip adduction and internal rotation compared to other dance genres such as Jazz, Contemporary dance, hip hop.

Adaptive shortening of the lateral hip joint capsule and external rotators occurs, which limits internal rotation. In addition, adaptive shortening of the gluteus medius and iliotibial band leads to limited hip adduction. These common patterns of movement lead to shortening of prime movers such as gluteus medius and leads to weakening of antagonistic muscle groups that control internal rotation and adduction.

Abnormal soft tissue adaptations at the hip have implications in injuries such as the snapping hip, iliotibial band syndrome, trochanteric bursitis, and potentially other lower extremity issues.

In classical dance forms such as ballet, Chinese dance and Bharatanatyam, the ideal turnout is achieved by a maximal external rotation of the hip, with smaller contributions from the knee, ankle, and foot joints. Dancers have remarkably increased range of hip external rotation compared to non-dancers. This is the result of bony and/or soft tissue adaptations. Being able to maximize hip external rotation will reduce the risk of injuries to the lumbar spine, and joints of the lower limb (e.g., knee, ankle). On the flipside, forcing turnout in dancers who lack sufficient hip external rotation may contribute to lumbar spine and lower limb injuries.

Hypermobile dancers (especially with hyperextended knees) may have episodes of knee pain when dancing with hyperextended knees, or when en pointe. Knee hyperextension relies on the joint locking out for stability, instead of muscular strength supporting the joint. This may lead to muscle straining and capsular and ligamentous spraining at the posterior aspect of the knee joint.

Flexibility

Flexibility training has increasingly been highlighted as an actual cause of injury in dancers. Askling et al (2005) found that of the elite ballet dancers who had experienced an injury in the rear thigh region, 91% of the injuries were located close to the ischial tuberosity (suggesting a proximal hamstring strain or tendinopathy). 88% of the dancers studied indicated that their injuries occurred during slow activities in flexibility training, such as front splits, and mostly in the warmup or cool down phase. Only 12% of injuries occurred during powerful movements such as grande jeté. This contradicts the findings in ball sports such as football, basketball whereby a muscular injury is most likely to happen during a sudden stretch.

Additionally, it has been shown that flexibility tends to be lower at the end of a dance season due to accumulated fatigue or burnout. This is in line with previous findings that dancers are more likely to experience overuse injuries towards the mid-end stage of the season. On the other hand, there seems to be a larger population of freelance dancers than company dancers in Singapore. Freelance dancers do not have off-seasons; hence they will have a slightly higher risk of accumulated fatigue leading to dance-specific overuse injuries.

Take a quick screen break before continuing on to the next section – it’s a long read!

DANCE SPECIFIC TRAINING

Strength

Basic principles

It has been suggested that muscle strength can play a role in reducing the risk of injuries in dancers. Strength training activates the brain to recruit more muscle fibres to work against the resistance applied.

Figure 1. Barry, Benjamin & Carson, Richard. (2004)

When resistance is consistently added over a period of time, the muscle fibres and neural pathways begin to adapt, making the muscle stronger and more efficient. An important strength training principle is overload, which includes intensity, duration, and frequency of training. Done properly, with recovery included, adaptation of the targeted muscle will occur. Muscles generally take at least 6 to 8 weeks to show significant improvements in strength.

Overload should happen in a gradual and progressive manner, whereby intensity, duration and frequency of the exercises are steadily increased.

An example of progressive overload:

Initial Stage | Progression | · Rest period of 60-90 seconds between each set · Avoid exercising the same body area on successive days e.g. lower body in sessions 1/3/5, upper body in sessions 2/4 |

2 weeks of high repetitions (15-25 reps) with low resistance – endurance focused | · Increase load with fewer repetitions (8-12 reps) – focusing on strength more than endurance |

Training for explosiveness and jumps

After seeing initial strength gains, we can incorporate explosive exercises to train muscular power.

Plyometrics training is a form of jump training in which maximal force is exerted in short intervals. An example of a plyometric exercise is 6-8 high tuck jumps, resting 30 seconds, and repeating for 2 more sets.

To apply progressive overload, number of repetitions may increase from 6 to 8 to 10 jumps, or increase the number of sets from 2 to 3 to 4 sets, and so on.

Other training principles to take into consideration: specificity, recovery, and reversibility.

Specificity – focus on the muscle (or muscle groups) associated with the action to gain strength. E.g. if you’re training for strength for lifting during partner work, you’ll want to target your biceps, deltoids, glutes and quads.

Recovery – the body adapts to overload (and new levels of fitness) during rest periods. Feeling fatigued or sore is expected. It is not always possible to feel 100% recovered before your next training session. Full recovery comes in during a planned deload or rest week.

Reversibility – consistency is key, as improvements achieved from training are easily lost without constant stimulus to maintain the results or continue progressing.

Aesthetic considerations

Strength training does not always equal to bulking up. One common misconception regarding strength training for female dancers is the concern that increased muscle bulk will negatively affect their overall aesthetic as a performer. For those looking to build strength without increasing bulk, strength training can be designed to improve neuromuscular function without compromising dance aesthetics.

Muscles consist of

· Slow twitch fibres – higher resistance to fatigue; meant for low-intermediate force production e.g. endurance based movements. These muscle fibres are activated with lower loads.

· Fast twitch fibres – fatigues more easily; meant for intermediate-high force production e.g. jumping, lifting. These muscle fibres require higher loads and demands to be recruited.

Genetics play a role in how much of each type of muscle fibre we have. I.e. “bulking up” is a process that takes many years for most men. It is a very common myth that women will gain too much muscle once they start strength training.

Some methods to minimize muscle gain (for aesthetic reasons), or if you do an endurance-based sport that requires you to be as light as possible:

· Compound movements

o Recruits multiple muscle groups across multiple joints

o Trains the body to move efficiently as a unit

o E.g. squats, deadlifts

· Heavy weights, low reps, more sets

o Aim for 85% of 1 rep max (1RM), 1-3 rep range

· Longer rest periods between sets

o Between 3 to 5 minutes rest per set

Hence, increasing muscular strength without increasing muscle bulk is possible but not indefinitely. At some point, muscle mass needs to increase to continue gaining strength.

On the other hand, if you are looking to maximize muscle bulk during strength training (aka hypertrophy):

· Increase the “time under tension”

o Minimum threshold for hypertrophy is ≧30% of 1RM

o Time under tension for hypertrophy: 30-60 seconds

o E.g., tempo 2:1:2 for 12 reps = 5 seconds per rep x 12 reps = 60 seconds time under tension

· Increase the total amount of weight lifted (moderate rep range, high number of sets)

o Repetition range between 8-12 reps

o 4-6 sets

o 1-2 min rest between sets

Eccentric strength

Eccentric strength training increases muscle strength in a lengthened position without losing power. Take a bicep curl for example:

· Concentric contraction: action of bending the elbow

· Eccentric contraction: action of extending the elbow

Having an emphasis on slowing down the eccentric phase of the movement increases the time under tension. This increases the metabolic processes that promote muscle protein synthesis (observed for 24-30 hours after training). Since muscles are weakest when they are maximally lengthened (based on the length-tension relationship curve), it is important for dancers to train eccentric strength both through-range and at end-range since dance choreography often involves big amplitude movements requiring both control and strength.

When incorporating eccentric strength training, stick to the weight and repetition range that you normally use for that exercise. Hence, you should be able to perform the exercise with consistently good form throughout each set before adding eccentric emphasis.

Side note: eccentric exercises can cause a lot of delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS), so start slow and avoid overdoing it during your first session incorporating eccentric exercises.

In a previous post (“The Importance of Strength Training for Dancers”), we looked at a few suggested training guidelines shown below. Thus far, there is no guideline created specifically for resistance training in the dance population, and most study protocols have been built on existing recommendations for strength training.

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommendations for strength training for healthy adults are as follows:

Focus | Frequency | Training Principle | Repetitions |

Strength | At least 2-3x/week with at least 48h separating training sessions for the same muscle group | 60-70% of 1RM, gradually increasing to ≧80% of 1RM | 8-12 reps, 2-4 sets |

Endurance | <50% of 1RM | 15-25 reps, ≤2 sets | |

Power | 20-60% of 1RM | 3-6 reps, 1-3 sets |

Now that we know more about minimizing vs maximizing muscle bulk as well as eccentric strength training, here’s a summary in table form for easier reference:

Focus | Frequency | Intensity | Repetitions |

Strength without bulk | At least 2-3x/week with at least 48h separating training sessions for the same muscle group | · ≧85% of 1RM · Compound movements | 1-5 reps, 3-4 sets 3-5 min rest per set |

Hypertrophy | · 60-80% of 1RM · Increased “time under tension” | 8-12 reps, 4-6 sets 1-2 min rest per set | |

Eccentric Strength | · Stick to same weight used for the exercise · Increase time under tension by slowing the eccentric movement | Same rep and set range for the exercise done |

Core strength

A study by Kalaycioglu et al. (2018) found that core stabilisation training performed for 45-60 minutes per day, 3 days a week, for 8 weeks achieved significant increases in several physical fitness parameters (such as jumping, proprioception, coordination, and dynamic balance).

The exercises consisted of mat-based core strength and Pilates exercises, as well as a Swiss ball, stability trainer, and dance-specific balance exercises performed on different surfaces with both eyes open and closed.

Exercise progression consisted of increased number of repetitions of the exercises and changing of the surface.

Pilates and/or Yoga

One question I’m often asked is, “Is Pilates or yoga sufficient for strength training?”

Short answer: No.

Long answer:

Both Pilates and yoga are considered bodyweight training. Pilates and yoga does benefit dancers looking to work on dance technique outside the studio as they often focus on the same muscle groups required during dance classes. Initially, there will be definite benefits such as increased strength, improved body awareness, and increased movement efficiency and control.

However, as the body adapts to the movement patterns of the exercises over time, the weight of the body will not be enough to overload the muscle, and will not be varied enough for muscle adaptation to occur.

Dancers should consider a varied routine of muscular strength training to increase overload and avoid muscular imbalance. In addition, improved muscular strength will allow dancers to have a better movement experience during Pilates and yoga classes.

Dance technique classes cannot, and should not, be the sole provider of conditioning exercises targeting physical fitness components such as strength, power, and endurance. Additional training outside of dance classes will allow us to perform dance movements with greater ease, such as jumping, lifting or catching a partner, or quick transitions from standing to floorwork. This in turn translates to greater capacity to explore new movements or stunts during choreography creation, as well as reduced risk of injury even with greater demands placed upon the body.

Mobility

Mobility exercises are different from stretching for flexibility (although end results may be similar). Recall that mobility is the ease with which a joint is able to move through a range of motion, and an indicator of the distance and direction the joint can move in. Mobility involves movement and motor control, which is how the nervous system coordinates the movement. Dancers who hold a lot of tension in your muscles and standing posture may feel constantly tight despite frequent stretching. Doing joint mobilizations can be helpful in breaking old patterns of movement without worrying about straining a muscle.

Recommended methods to improve mobility:

· Controlled Articular Rotations (CARs)

o Active rotational movements done at the end range of motion of the relevant joint to stimulate articular adaptations.

o The controlled tension during the movement improves kinesthetic awareness and joint stability.

o Example of a hip CAR (https://youtu.be/SNyXBq30VuQ?si=_yqUENPILdtoZWLU)

o Aim for 3-5 reps per joint, daily.

· Myofascial release

o The fascia surrounding our muscles can thicken (due to dehydration, or genetics) and inhibit the function of the surrounding tissues, which impacts joint mobility. Applying sustained pressure (with foam rollers, tennis balls etc) can help to reduce the adhesions and allow the muscles to function better.

· Strengthening the “opposite” muscle

o Using the principle of reciprocal inhibition (when one muscle, the agonist, contracts, the muscle that does the opposite movement, the antagonist, has to lengthen to allow movement at the joint)

o E.g., hip flexion: agonist – hip flexor, antagonist – hip extensor (glutes). To lengthen the hip flexor, we would then incorporate exercises with hip extension as the primary movement e.g., bridging, reverse Nordics.

Flexibility

To increase career longevity for dancers, we need to understand and promote a balance between muscular strength and flexibility.

Static vs dynamic stretching

Static stretching will provide the flexibility required when doing a leg hold or gravity-assisted split. Studies show that the total volume of stretch matters more than the format, i.e., whether it is a 120-second static hold vs 6 sets of 20 seconds, there is no significant difference in improvements in muscle length between the two.

The normal stretch feeling comes from muscle contraction at the end range of a joint movement to prevent further movement. This “safe limit” is designed to protect the muscle, joints, and surrounding soft tissue. When we try to push past this “safe limit”, the muscle tightens and hence we feel a stretch. Overstretching may leave the muscle feeling tighter and possibly weakened. Forced stretches will stretch the protective ligaments around the joint instead of the intended muscle, as well as putting significant stress on the joint. These contribute to increased risk of pain, impingement, or instability, which may lead to future injuries.

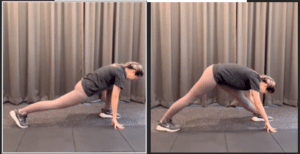

To translate that flexibility into gravity-resisted movements such as grand jetés, leg kicks, or développés, dynamic flexibility is needed. Common dynamic stretches are leg swings (in lying or standing), deep lunge into lunge stretch and back to deep lunge.

As a rule of thumb, dynamic stretches move the targeted joint through the full range of movement and aim to increase the end range a little more with each repetition. Dynamic stretches are a good way to warm up, however the effects achieved are short-term and do not carry over after the training session is over. On the other hand, eccentric strength training has been shown to effect changes in the nervous system and muscle fibre structure, which allows for increased length during active movement without losing power.

Eccentric strength for flexibility

Using eccentric movements to strengthen the relevant muscle sends a signal to our nervous system: that our muscles have the strength to cope with a greater range of motion. If you have had any previous strains (e.g., hamstring, adductors) that just doesn’t seem to recover fully, training eccentric strength in the range of movement that you were injured in may help. For example, if you strained your hamstring from oversplits or after doing a high kick, start eccentric strength training in a smaller, pain-free range (e.g., hamstring curls, hamstring bridge) before increasing the range (e.g., Romanian deadlifts, straight leg hamstring bridge).

Instead of solely relying on repeated passive stretching to improve flexibility, we encourage a combination, with a primary focus on eccentric strength (with a gradual overload), followed by static stretches at the end of the training session when muscles have been sufficiently warmed up.

Conclusion

Improving muscular strength and joint mobility are important in preventing dance injuries. To dance and move in extreme ranges of motion requires strength and control; majority of dancers require strengthening rather than stretching. Flexibility without strength often contributes to dance injuries.

Train smarter, not harder – identify weak areas and work on them outside of dance trainings and rehearsals.

References